Funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3, Theme 10.

Past and future of the Mediterranean Diet: how models can adapt to local needs

An innovative approach to the Mediterranean diet, adapted to local resources, shows how it is possible to promote health and sustainability while enhancing the nutritional specificities of the territory.

Federica Cantelli

Researcher at University of Naples Federico II

The Mediterranean diet, recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, is much more than just a dietary regimen: it is a true lifestyle that promotes health and well-being. Its origins are very ancient, but the term "Mediterranean diet" is relatively recent.

It was coined by the American physiologist Ancel Keys, who, during the 1960s, identified the dietary habits of the inhabitants of Greece, southern Italy, Spain, and other geographical areas of the Mediterranean basin through research and travel. These pioneering studies allowed Keys to associate the dietary patterns and lifestyle of the inhabitants of this region with longevity and low mortality rates from coronary heart disease, cancer, and other diet-related chronic diseases that characterized them.

Although referred to as a "diet," the Mediterranean diet goes far beyond the local, zero-kilometer food model that characterizes it, incorporating traditions and ways of life as well. A common element among many of the populations Keys studied was highly dynamic work and an active lifestyle.

For instance, the fishermen of Pollica, a town in the province of Salerno where Keys worked for an extended period, would walk long distances daily to reach the sea. Despite being a demanding and exhausting job, it was an integral part of their way of life.

An active lifestyle, like that of the fishermen of Pollica, brings numerous health benefits. Walking daily and engaging in consistent physical labor improves cardiovascular endurance, strengthens muscles and bones, and increases lung capacity.

Furthermore, regular physical activity helps manage body weight, reduces the risk of chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, and positively impacts mental health by lowering stress and improving mood. In many of the communities Keys analyzed, the combination of physically demanding work and a dynamic daily routine translated into a superior quality of life, with remarkable longevity compared to other populations.

Dynamic work and active lifestyles were not the only commonalities Keys observed among the various populations he studied. Their relationship with food was also characterized by its social dimension.

In Mediterranean culture, eating is not merely an act of consuming the calories necessary for the body's energy needs but a fundamental moment in the life of community members. It is a time of sharing and conviviality, whose importance and ancient roots were emphasized by the Greek historian Plutarch, who wrote about the act of eating:

We do not sit at the table merely to eat, but to eat together.

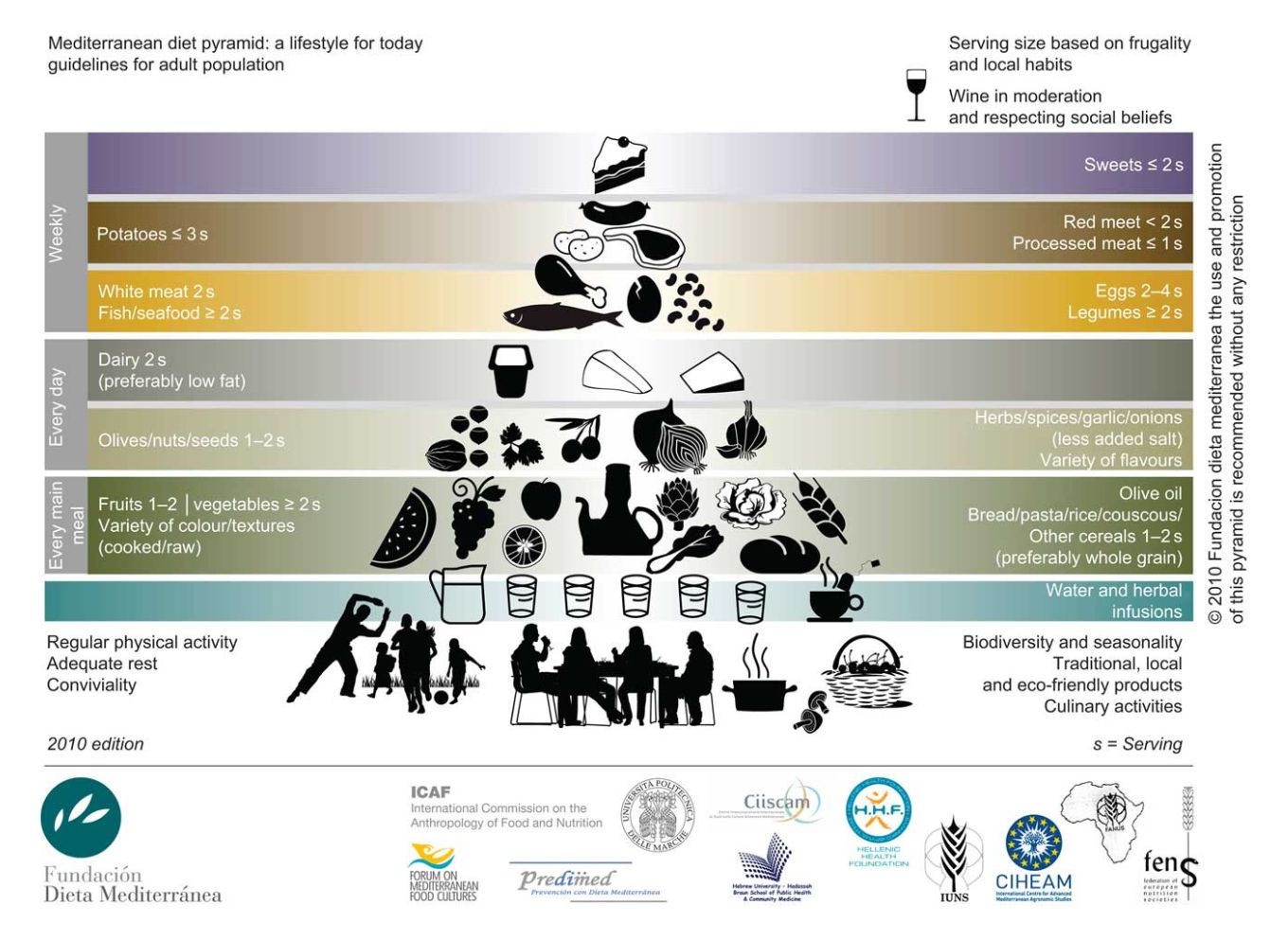

The foods that characterize the Mediterranean diet are numerous, all represented in the Mediterranean diet pyramid.

Extra virgin olive oil (EVO) is at the heart of the Mediterranean diet. Thanks to its monounsaturated fats and polyphenols, it helps lower bad cholesterol (LDL), increase good cholesterol (HDL), and protect cells from oxidative damage. Alongside olive oil, fresh fruits and vegetables play a key role, being rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that help prevent diseases like diabetes and cancer.

From tomatoes, full of lycopene, to citrus fruits with vitamin C, and spinach and kale rich in micronutrients, every food offers a unique contribution.

Whole grains, such as rice, wheat, and spelt, provide long-term energy through complex carbohydrates and improve digestion thanks to their fiber content. Legumes, such as beans and lentils, are equally valuable: a sustainable source of plant-based proteins and allies for heart health. Oily fish, like sardines and mackerel, are rich in omega-3s, which are essential for reducing inflammation and maintaining heart health. Similarly, nuts and oilseeds, in addition to being a tasty snack, provide healthy fats and nutrients that enhance overall well-being.

Red wine also has its place, provided it is consumed in moderation: its resveratrol content is a powerful antioxidant beneficial for heart health. Finally, in the Mediterranean diet, red meat is kept to a minimum, while white meat and low-fat dairy products are preferred, striking a balance between taste and health.

Consuming zero-kilometer or short-supply-chain foods offers multiple benefits: freshness, the absence of chemicals and fertilizers that could compromise flavor and health, and the preservation of organoleptic properties due to minimal transport. Additionally, seasonal fruits and vegetables provide particularly high nutritional value.

When Keys conducted his research, he encountered populations whose ways of life had remained virtually identical to those of their ancestors or had changed very little. Since then, the rapid acceleration brought about by modernity has led to significant transformations in the lifestyles of the populations studied by Keys.

Globalization, for example, has made nearly all foods available year-round, often at the expense of their seasonality. At the same time, the rise of the food industry has increased the consumption of processed foods, putting many local culinary traditions at risk of disappearing.

The spread of processed foods reflects the demands of increasingly fast-paced lifestyles, where work is no longer tied to the rhythms of the seasons but dictated by the tempo of production. This shift has also made life more sedentary, facilitated by the widespread use of transportation—cars in particular—which makes travel easier but drastically reduces walking and contact with nature.

Similarly, the social and shared dimension of food has also diminished. New work rhythms and demands make it increasingly difficult to sit at the table together, and the act of eating in company and conversing has been replaced by meals at the computer, at the desk, or in front of the television.

Aware of the health consequences of the constant availability of food and the excessive consumption of processed foods, younger generations have recently been placing increasing importance on a healthy and sustainable diet, sparking renewed interest in fresh and organic foods typical of the Mediterranean tradition.

The profound benefits of this diet have even led some researchers to question how to make this ancient dietary model accessible to the widest possible audience, including those outside the geographical area where it originated, while avoiding the more apparent negative externalities of globalization. These include, for instance, the export of foods typical of the Mediterranean basin to other parts of the world, undermining the principles of seasonality and local sourcing and disrupting other culinary traditions by replacing them with Mediterranean ones.

Planeterranean Diet: The Future of the Mediterranean Diet

The solution currently under study to achieve this ambitious goal—spreading the Mediterranean diet worldwide while adapting it to the typical foods of each region—is to transform it from Mediterranean to Planeterranean.

In the preliminary study on the Planeterranean diet conducted at the University of Naples Federico II, the starting point was to divide most of the globe into five macro-regions: North America, Latin America, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

In a subsequent study, aimed at creating the pyramid for the Planeterranean diet in Asia, each macro-region was further subdivided into smaller areas with similar soil and climate conditions. For the Asian continent, six regions were identified: Central, East, North, Southeast, South, and West.

Once the dietary habits of a specific geographic area are understood, researchers examine the nutritional characteristics of typical foods from that region to assess their effects on human health. Based on their composition and health effects, these foods are substituted for those in the traditional Mediterranean diet, providing similar benefits through different ingredients.

From a Planeterranean perspective, for instance, avocado can replace extra virgin olive oil for populations in Central America, while certain algae can substitute nuts and oily fish as sources of polyunsaturated fatty acids for some Asian countries. In Central Africa, local grains like cassava and teff support the production of short-chain fatty acids, beneficial for gut microbiota.

Additionally, the use of quinoa in South America serves as an excellent example of a high-protein food rich in essential amino acids, which can replace the whole grains typical of the Mediterranean.

The authors of these studies propose the creation of "local nutritional pyramids," dietary models that mirror the traditional Mediterranean diet pyramids while adapting to the geographic and cultural contexts of various regions worldwide. Each pyramid is structured around locally available foods, preserving the key nutritional properties that make the Mediterranean diet effective in preventing chronic diseases and promoting overall well-being.

This approach acknowledges the unique characteristics of each geographic area. For instance, in tropical countries, fruits like papaya and mango could serve as key sources of vitamins and antioxidants, while whole grains and plant-based protein sources such as beans and maize would replace their Mediterranean counterparts.

In regions like North America, nuts such as pecans and canola oil could play a role similar to that of olive oil and Mediterranean almonds, providing heart-healthy monounsaturated fats.

This initiative not only encourages local populations to rediscover and appreciate their traditional foods but also promotes a sustainable dietary model. By reducing reliance on imported products and emphasizing a low environmental impact, the Planeterranean diet contributes to both health and sustainability.

Federica Cantelli

Researcher at University of Naples Federico II