Funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3, Theme 10.

Women in Science, Women of Science: OnFoods for the International Day of Women in Science

Scientific disciplines serve as a crucial gateway to strategic leadership positions in society, yet the path toward formal and substantive female representation remains long. The International Day of Women in Science reminds us of the importance of real progress in women's careers.

Giulio Burroni

Communication manager

Scientific disciplines serve as a crucial gateway to strategic leadership positions in society, yet the path toward formal and substantive female representation remains long.

The International Day of Women in Science reminds us of the importance of real progress in women's careers. Only through such advancement can we achieve a meaningful female presence in companies, research institutions, and key sectors of technological innovation.

To draw due attention to the connection between science and gender, February 11 marks the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, established in 2015 by UNESCO in collaboration with other partners. This occasion aims to raise awareness of the importance of a more equitable participation of women in the scientific and technological fields while highlighting, year after year, both progress made and ongoing challenges.

In 2025, the central event, titled "Unpacking STEM Careers: Her Voice in Science," will focus on advancing gender balance in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), not only in terms of numbers but also in the quality of opportunities available. As the title suggests, the goal is to amplify the voices of women working in science, shedding light on persistent disparities and proposing concrete solutions to overcome them.

OnFoods draws inspiration from this significant UNESCO initiative, not merely to celebrate it but to launch a broader reflection—one that begins today and will continue in our magazine through in-depth analyses and interviews. Let’s begin.

STEM! Still the Steepest Climb

The so-called STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) are widely regarded—rightly or wrongly, and certainly at the expense of many other disciplines—as the primary drivers of technological, economic, and social development.

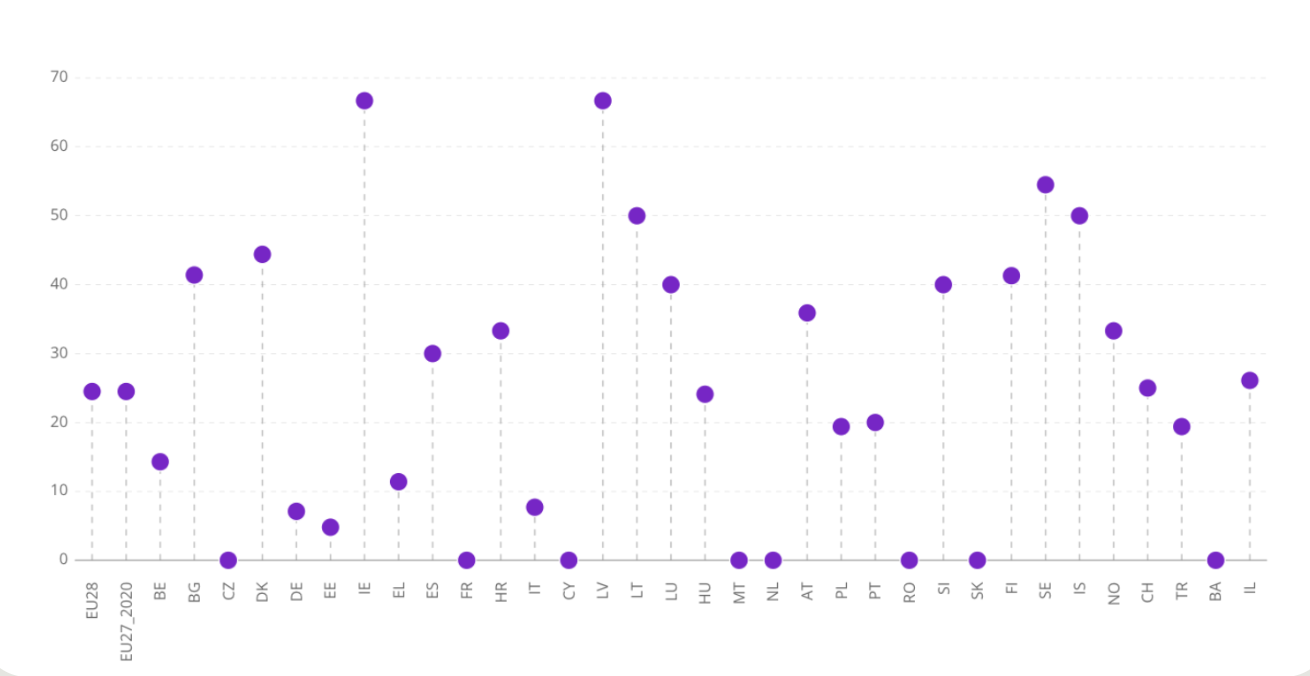

Yet, these fields remain deeply marked by gender disparities. The global data speaks volumes: according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, women account for less than 30% of researchers worldwide. In Italy, the situation is slightly better: out of 136,000 researchers, approximately 47,000 are women, representing 34% of the total. However, the gender gap emerges early in education: globally, only 30% of female students choose to pursue studies in STEM fields (UNESCO). This imbalance is also reflected in national policies: in 2016, only 30% of countries with available data had achieved effective gender parity in the scientific sector.

The issue is not only about access but also about career progression and recognition. Although numerous studies show that men and women achieve equivalent results in STEM, cultural stereotypes continue to discourage many young women from pursuing these careers. Social expectations still tend to steer young men toward technical and strategic roles while relegating young women to positions perceived as less central or prestigious. This social conditioning takes root early in education and becomes even more pronounced in professional trajectories.

Even when women manage to enter the STEM world, they often encounter obstacles that hinder their advancement: female representation drops sharply in top leadership roles, where men remain overwhelmingly dominant. A striking example of this disparity is found in the Nobel Prizes: to date, only 22 women have received this prestigious award in scientific fields, compared to hundreds of male laureates. And as many already know, this gap is not merely the result of lower numerical participation but reflects deeper mechanisms, such as the Matilda effect—a phenomenon that describes the systematic undervaluation of women's contributions to science. This practice not only denies female scientists the recognition they deserve but also perpetuates a cycle of invisibility.

As we will see, the lack of strong and visible female role models has a ripple effect on younger generations, discouraging other young women from considering STEM as a viable and rewarding career path.

Not All That Glitters: The Medical and Life Sciences Sector

While gender parity issues are particularly pronounced in STEM disciplines, the discussion cannot be limited to these fields alone. A broader analysis should encompass the entire spectrum of disciplines, including those that are more interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral—such as the medical and life sciences, which are at the core of the OnFoods partnership.

Looking at the data, women have a strong presence in the early stages of academic careers in the medical and biological fields, accounting for over 70% of research fellows in medical sciences and 66.2% in biological sciences.

However, even in these sectors—much like in STEM—a significant decline is observed in leadership roles and full professorships, leading to an undeniable conclusion: structural and cultural barriers continue to hinder women's advancement to top positions, despite their crucial contributions to medicine, biology, and related sciences.

Medicine has historically been one of the most "feminized" fields in terms of enrollment and academic participation. In Italy, for example, over 60% of medical students are women. However, this representation drops drastically at the level of department heads and leadership positions in healthcare.

This reality is also confirmed by the experience of Professor Anna Maria Colao, coordinator of Spoke 5 of OnFoods and Head of Endocrinology at the University of Naples.

"Despite the strong presence of women in medical degree programs, it is clear that the so-called ‘glass ceiling’ is still firmly in place in healthcare careers," says Colao. "Women struggle to reach top positions, such as department head roles, or leadership positions in research institutions and hospital management. This is not due to a lack of competence but rather to systemic, cultural, and organizational barriers that continue to hold them back. And this is not just a loss for individual professional careers—it is a shortcoming that weakens the entire healthcare system. When female leadership is not valued, we lose the opportunity to build a more equitable, inclusive, and responsive healthcare system, capable of addressing the needs of an increasingly diverse society".

The PNRR and the 40% Thresholds: What to Expect in the Near Future

The ONFOODS project, which involves around 600 people, has placed a strong emphasis on gender equality from the outset, aligning with the recommendations of the UNESCO Science Report: Towards 2030 and the requirements of Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR).

The UNESCO report highlights numerous factors that contribute to the gradual decline of female representation in scientific careers. Among these are the glass ceiling, the so-called maternal wall, inequitable evaluation criteria, the undervaluation of leadership roles, and often unconscious gender biases.

"When it comes to careers," comments Hellas Cena, Vice-Rector for Third Mission at the University of Pavia and coordinator of Spoke 6 of OnFoods, "we see good female representation in biological sciences, but at the top levels, the imbalance is still evident. The number of female full professors, for example, remains insufficient compared to their male counterparts. Despite this disparity, the ongoing change—though it needs to accelerate—is undeniable. We see it in the growing number of female rectors currently in office at Italian universities, in department directors, and in research center leaders. A transformation is certainly underway, but ensuring that it becomes substantive rather than merely formal is imperative."

Aware of these challenges, OnFoods has launched a series of initiatives aimed at promoting gender equality at every stage of the project, from personnel selection to activity management. Particular attention has been given to recruitment, with the goal of ensuring that at least 40% of the staff—including research fellows and PhD candidates—are women. To encourage greater female participation, the project has adopted more inclusive recruitment practices, such as using gender-neutral language in job postings and promoting opportunities through targeted platforms.

"The recruitment process within the OnFoods project," comments Professor Daniele Del Rio, President of the OnFoods Foundation, "has far exceeded the 40% targets set by the PNRR. This was also possible because our disciplines have historically been more gender-balanced. However, we are already seeing that a portion—though not yet a large one—of the young talents recruited is now entering the promotion and contract consolidation phase."

Beyond the numerical targets, Patrizia Riso, President of the OnFoods Scientific Committee, coordinator of Spoke 4, and full professor at the University of Milan, highlights a broader perspective:

"Our goal at OnFoods is not just to meet the thresholds set by the PNRR, but to create a working environment that values female expertise and fosters a genuine culture of equity. Moreover, there is another crucial aspect of gender that we must address from a scientific perspective: we can no longer overlook gender dimensions in the very content of our research. Gender differences are deeply intertwined with our areas of study, such as nutrition, health, and the social impact of supply chains."

The topic is crucial: considering sex and gender in scientific research helps ensure more accurate and representative results, thus improving the health and well-being of all people. In this regard, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States has introduced guidelines to promote the use of sex-disaggregated data and gender equality in scientific research.

The goal is to ensure that biological and gender differences are properly considered in the design, analysis, and interpretation of scientific studies, with the aim of improving the quality and applicability of results for both sexes. For example, the "Sex and Gender in Health and Disease" group at the NIH promotes the exchange of information and interaction among scientists interested in sex-based research aspects.

"The gender-sensitive approach," continues Riso, "is particularly relevant in the paradigm of one of my research fields: personalized nutrition. We know that nutritional needs and metabolic responses can vary significantly between men and women, not only for biological reasons but also due to cultural, social, and behavioral differences. Ignoring these specificities means risking proposing solutions that do not truly address the needs of a significant portion of the population. Incorporating a gender perspective into personalized nutrition, therefore, is not just an issue of equity, but a fundamental step in improving the effectiveness and impact of nutritional strategies on both an individual and collective scale."

Beyond access and contracts: the voice of women in science.

When discussing gender equality in science, it is not enough to focus solely on data regarding access and contracts to provide a comprehensive picture. It is crucial to also consider two additional key aspects: dissemination, which refers to the body of publications that form the essence of scientific discourse, and communication, which involves how science fits into and is perceived in the public debate.

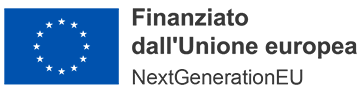

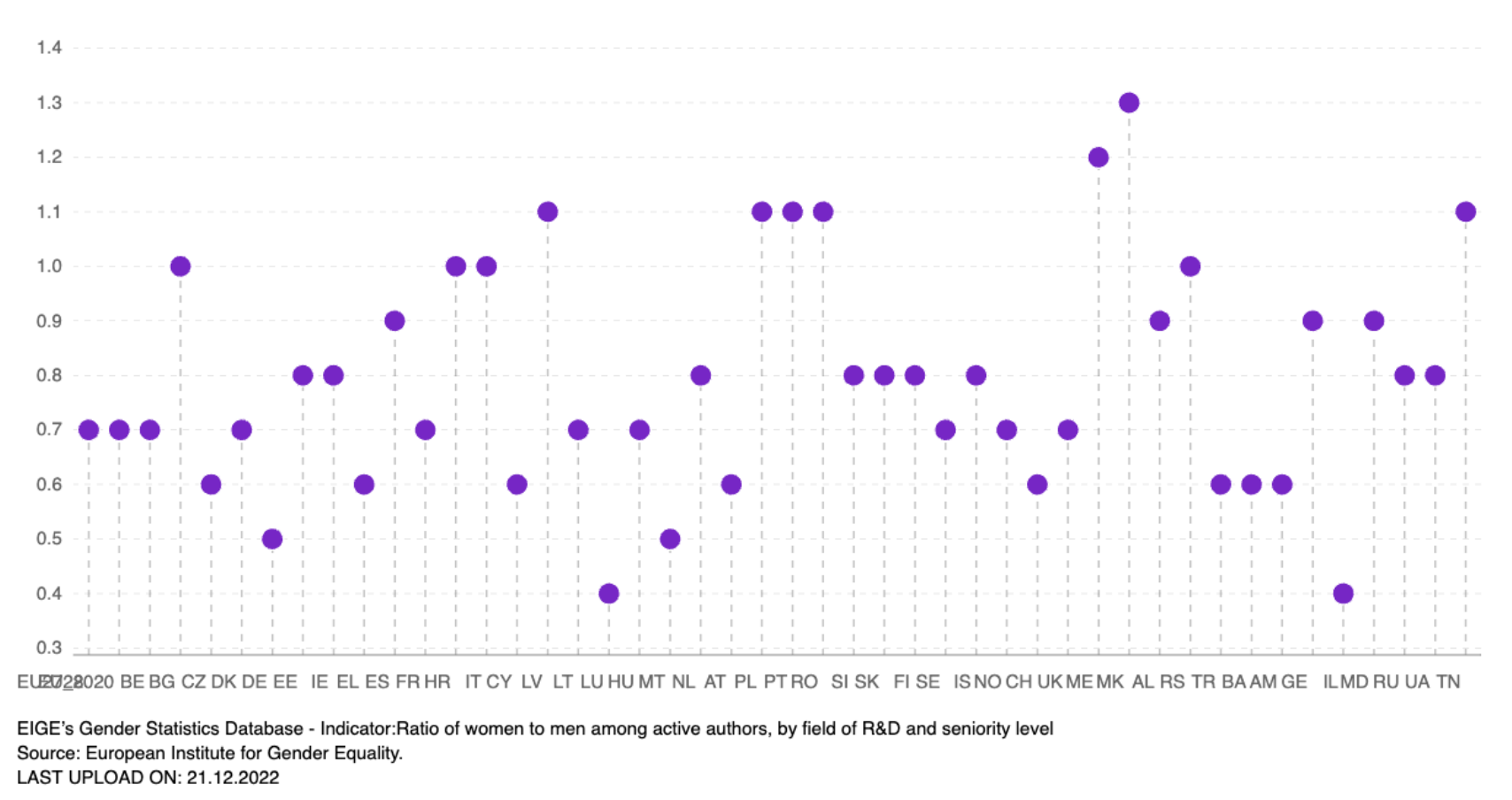

The numbers on scientific publications are important and can tell us a great deal: who signs the articles, in what roles, and on which topics? And, most importantly, how do these details reflect the gender gap within the academic community?

Bibliometrics, which analyzes scientific output through the systematic study of publications, citations, and authorship positions, is the primary tool to address these questions. However, numbers alone are not enough: behind the figures lie stories of inclusion – or exclusion – that deserve exploration to truly understand the gender dynamics in the academic world.

One of the most relevant and studied aspects in the literature is the position of "last author," typically associated with senior roles and leadership in research projects. Studies conducted in the medical-biological sector, for example, show that many women occupy the position of first author, which ensures them good visibility. On the other hand, this signals a disparity in leadership roles, as the last author position is generally associated with seniority.

However, bibliometrics allows for the analysis of many other dimensions. Which areas of research receive the most contributions from women? What is the frequency of collaborations between male and female authors? How are citations distributed, and which mechanisms amplify or penalize the visibility of women’s work, such as the phenomenon of self-citations? Additionally, it is possible to explore how funding, awards, and academic recognition are distributed by gender, and how this influences career trajectories.

“The merit of this kind of study,” continues Hellas Cena, “is not only to quantify inequalities, but also to provide a foundation for reflecting on how to reduce them. Why are these analyses important, then? Not only to register progress or shortcomings, but to identify critical points and build more effective policies that promote equitable representation. In short, if we really want to imagine a more inclusive academic system, we must start here, with the questions raised by the numbers and the answers we can build together.”

The other side of the issue: women scientists in public debate.

The other side of the problem concerns how the media represent women in science and how they manage to insert themselves into the public debate.

Media visibility is not just an issue of individual recognition but a key factor in redefining the collective imagination and breaking down gender stereotypes that still relegate women to secondary or marginal roles. Without a constant and impactful presence in spaces where opinions are formed – from talk shows to interviews on current issues, to broader cultural narratives – female scientists risk remaining isolated voices, excluded from decision-making processes and from the opportunity to influence the future of research.

This absence, in turn, fuels a cycle of invisibility that also reflects on the perception of younger generations, depriving future female researchers of strong and attainable role models.

Silvia Lazzaris, an investigative journalist also specializing in science communication, speaks to this issue:

“In journalistic pieces,” she tells us, “it is often men who are more willing to respond to interview requests or to present themselves as experts. Women, on the other hand, and from my personal experience, tend to be more hesitant, perhaps for fear of not being perceived as authoritative enough or of ‘invading a space’ they don’t feel legitimately belongs to them. This generates a vicious cycle, a sort of echo chamber, where the male voice continues to dominate and strengthen, while the female voice remains marginal. However, the solution cannot be reduced to a simple numerical inclusion: there needs to be an empowerment effort for female scientists, so they feel more confident in participating in the public debate, and at the same time, the media must actively commit to seeking and valuing female voices, breaking this self-perpetuating dynamic.”

In the end, achieving gender equality in science means changing things at every level—from leadership opportunities to proper recognition in research and media. It takes a collective effort to create an inclusive environment where women’s contributions are valued, allowing female scientists to drive progress and help shape a more equitable society.

Giulio Burroni

Communication manager

Specialist in Communication and Project Management with over 8 years of experience in agency work. Currently involved in communication, branding, and design projects within the public administration, research institutions, and university sectors